Debunking Monking Part I: what lures a Brit into Buddhism

Monks – what are they? What is this Buddhism thing they profess? What relevance does it have to Thai society? These are some of the questions I will attempt to answer in this series of articles. And what do I know? Well, I am one, so I know whatever it is that a monk knows. Of course that also means that I’m likely to be smuggling in some blatant Buddhist propaganda under the convenient cover of writing a usefully informative, cultural-interest piece. You have been warned.

For this first instalment, I’ll start by looking at that first, rather fundamental question.

“Monks – all is burning. And what is the all that is burning?”

The Fire Sermon, Samyuta Nikaya 35.28

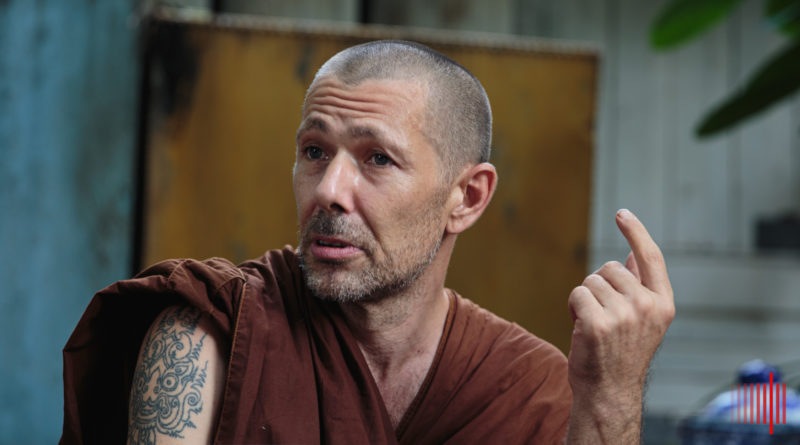

Well, for a start, this is a monk:

I had a fairly typical upbringing in England. You can assume monks weren’t really something that I thought about much, if at all. Not until I saw this picture for the first time. Malcolm Browne, its photographer, won World Press Photo of the Year in 1963. A deserving win, particularly considering his excellent news-hound instincts in being one of only two foreign journalists who had bothered to show up to document an event which had a resounding impact across the world.

It certainly had an impact on me, although I wasn’t around in 1963. By the time I saw it, it had passed into the common cultural iconography of “generalised images of resistance”. Similarly to that screen-print of Che looking all bedraggledly handsome and far-seeing, some quality in the image itself kept it alive. Long after people who stuck posters of it on their walls had mostly become a bit hazy about what it meant.

Most people under 40-something now probably associate it with the cover of Rage Against The Machine’s 1992 debut album. That album also had quite an impact on me, although not in the same life-changing way. Otherwise, rather than this comfortable orange robe and buzz-cut, I might instead be dressed like Zach de la Rocha. It’s just as well that I’m not, since dreadlocks on a white guy are rarely a good thing (albeit that message has yet to filter through to Koh Samui). Worthy as RATM’s recycling of this powerful image was, it’s perhaps worth briefly refreshing what precisely happened here:

In 1963, Vietnam had won the Indo-China War and ceased to be a French colony. But it still wasn’t a happy time – the country had split into the Communist North and the Capitalist, Catholic South. The government was controlled by a clique of Western-orientated strongmen, still trying to hang on to power even after independence. This ruling clique had converted to be more French and sophisticated. They adopted increasingly brutal repressive measures to force Vietnamese to do the same. Buddhism, and traditional culture in general, appeared to them as a rallying point against their minority rule. They also accused the Buddhists of having Communist links, which played well with their American backers. During one annual festival of Visakha, the Army opened fire and drove vehicles into a crowd of Buddhists. The carnage resulted in the death of nine people, including two children, and many more casualties.

Some days later, a procession of monks and nuns moved through the streets of central Saigon. They stopped the traffic at a busy intersection and formed a circle. In the middle, Thich Quang Duc, an eminent meditation teacher in his mid-sixties, sat down in the lotus position. Another monk poured five gallons of fuel over him and handed him a box of matches. He struck one, and then Malcolm Browne snapped this picture.

Actually, Browne took quite a few pictures, and there’s also a grainy and shaky video. It’s worth looking at all of them to get a sense of the unfolding event. In this iconic one, the wind blew strongly enough to reveal Quang Duc’s face amidst the smoke and flames. Take a close look at it. There might be tightness around the mouth, but no more than you’d expect to see with anyone holding their breath under less drastic circumstances. His posture is also worth noticing. A look at the whole sequence will show that he starts out with a straight back and at a certain point begins to slouch. Then he corrects himself and remains perfectly straight until he dies and falls over. There’s something much more, or just other, going on here than commitment and toughness.

This action was partly a shock-theatre, calling the world’s attention to injustice in a small country most people outside Asia had probably never heard of. The endeavour succeeded, as the picture dominated newspaper front-pages around the world. It was also a resounding demonstration that the spirit of Buddhism was immune to intimidation, and could not be suppressed by force. And it wasn’t only him. Over the following weeks, five more Vietnamese monks also burned themselves in much the same way, showing similar equanimity in the face of fear, pain, and death.

The results of these actions were swift and profound. President Kennedy withdrew support for the regime. It was then toppled by an internal coup shortly afterwards, and the persecution of Buddhists ended. But that’s all by-the-by since I didn’t bring this up to discuss the political consequences. Let’s return to that face in flames.

There are many aspects to what happened here – courage, moral conviction, sacrifice, for instance – which it could be argued are extraordinary. Yet, it would be no more than what you might find in fanatical suicide bombers, hopped up on indoctrination and the promise of heavenly delights. It’s the evident impassiveness and calm that makes this clearly different. That is what makes it, in fact, almost incomprehensible. How could he do that? That was the question that burned itself into my mind when I saw this monk burning. I am still trying to answer that. I look at this picture a lot – it’s the screen-saver on my computer, as it has been for nearly twenty years.

But what was immediately, abundantly, unarguably clear to me even back then was that Buddhists might reasonably claim to be onto something. Something real and non-theoretical. They weren’t just bandying about unprovable, high-falutin’, metaphysical speculations, based on little more than tradition, and faith in ancient words claimed to be from on-high. Whatever they might claim to know was clearly based on the far more concrete evidence that modern-day practitioners could use it to transform themselves in ways unimaginable to me.

At this point, I would love to say that, inspired by this extraordinary image, I set out on a relentless quest to find the source of this strange power. I left trivial worldly matters behind, overcame dangers and obstacles, accepting no discouragement or cheap substitutes. After several gruelling years schlepping up snowy peaks and meditating under icy waterfalls, I eventually found the Yoda-like spiritual master who unlocked these mysteries.

The truth is more akin to – being at that time a young and narcissistic doofus, I somewhat hastily processed this paradigm-shattering data and filed it away in the drawer marked “Things that might be occasionally useful for giving an impression of intellectual and emotional depth, probably although not exclusively for the purpose of getting laid.” Long name – large drawer. And there it resided for many years, although it did get occasionally dusted off because I could never unsee that image, or forget my niggling curiosity about it.

It’s probably safe to say that it never directly contributed to any instance of me getting laid. What I can definitely say is that it was a huge influencing factor when, years later, I first properly encountered Buddhism and the monkhood here in Thailand, and quite quickly decided to, well at least “dip a toe in the water” as I then thought. There were other more immediate factors – which I will get to – but the ground was prepared, and the way opened, largely as a result of this one image of Thich Quang Duc on fire, and being apparently okay with that.

Charoen Porn

Debunking Monking will be published every full moon and new moon. Part II will be out on Saturday 20 June. Stay tuned!

About the author

Phra Peter Suparo

History geek. Enjoys sitting around doing as little as possible. Semi-retired bon viveur. Eternal student. Elf-friend. Theoretically in favour of humanity.