Hidden slums: neglected nooks of Bangkok

In cracks between city skyscrapers and malls, impoverished mass resides in squalid, cramming areas known as slums. Most people know of the Bon Kai community, Baan Krua community, and the notorious Klong Toey–largest slum in Bangkok. COVID-19 strikes the already decrepit slum dwellers, financial-wise and livelihood-wise. Yet residents of these communities receive occasional aid from government-led and foundation-led projects.

Meanwhile, countless other “hidden slums” in Bangkok are suffering the same problems, but without similar outreach.

The edge of inequality

At least 1,000 unsurveyed slums with 20-30 households scatter over Bangkok, according to Sittiphol Chuprajong, head of the Mirror Foundation’s homeless project.

Residences in these communities are not registered with Bangkok district offices. As a result, dwellers are overlooked and do not receive state assistance.

“Most people in society are oblivious of these slums’ existence throughout Bangkok. Help, therefore, could not reach these people. Assistances from projects and donations concentrate on larger, better-known communities,” said Sittiphol.

Early occupants were rural-to-urban migrants looking for more promising opportunities in Bangkok. Many became unskilled factory workers. After closures of various factories, lack of capital and access to land prevented the workers from returning to hometowns. They continued dwelling in the nooks and crannies of the city.

Poverty is expensive

Behind Wat Rat Satthatham in Khan Na Yao district lies an unnamed community of 24 households. Mee Boonnisa, the community’s de facto head, said that their public utility expense is higher than normal residence. The rates of electricity and water per unit are costly because the residents have to connect them from registered houses.

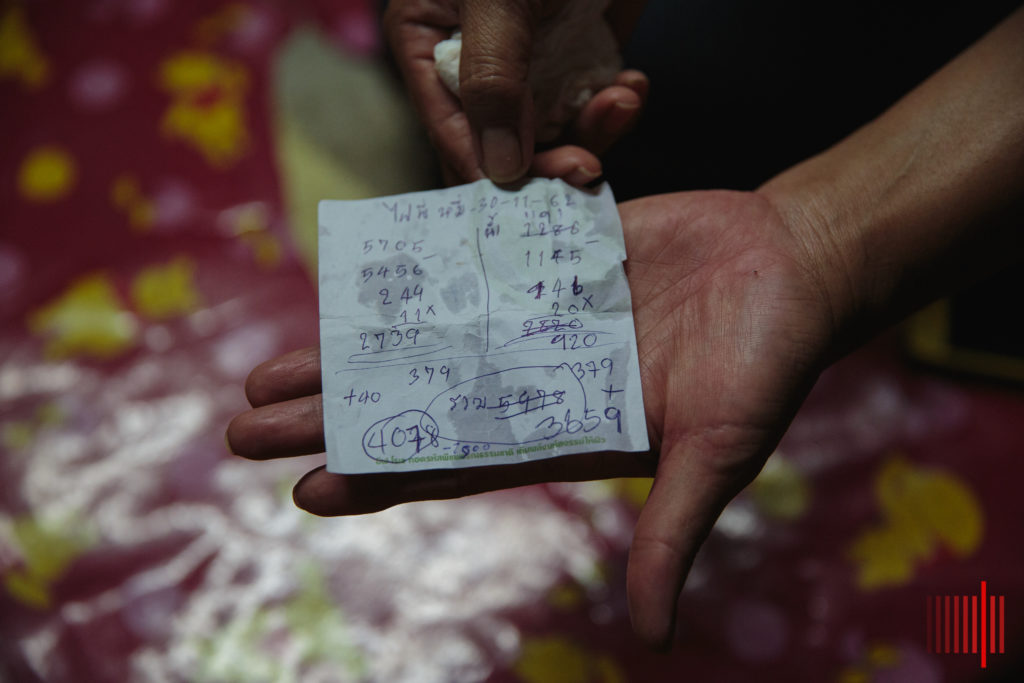

Mee herself owns two fans, a television, a refrigerator, and a rice cooker. Despite modest appliances, she has to pay 2,000-3,000 THB per month for electricity. The homeowner whose house rents out utility charges 11 THB per unit for electricity and 20 THB per unit for water. Mee needs to save up 3,000-4,000 baht for monthly utility bills.

“My mother’s bill was 4,500 THB. In some hotter days, she doesn’t even use the tiny fan she has. She uses a hand fan, saying she would rather not burden my brother. Because he is the only one who still gets to work,” said Mee, showing the electricity bill.

During the COVID-19 crisis, Mee’s income dwindled.

“I work at a factory. When the factory could not export the products and did not need workers, my income disappeared. The homeowner came to collect the electricity fee, and I shamefully could not pay them. I know they have to pay for the electricity they rent us, but we really cannot pay. I used to earn a salary; today, I do not. My kid just entered secondary school, so that takes money. I have other debts too. Typically, I barely have any money left at the end of a month. Now I do not even have enough.”

Community members supported Mee’s statement; they have no choice but to pay the overpriced utility bills rented by other houses. They do not ask for free electricity and water, requesting only to be charged with a standard rate.

Left behind citizens

Recently, the government carried out “Rao Mai Ting Kan” (We Do Not Leave Anyone Behind) compensation scheme. Citizens in need who meet the criteria are to receive a monthly 5,000 THB cash aid for three months.

Unfortunately, slum dwellers could not access this much-needed aid.

Ma Long community, another slum not far from Wat Rat Satthatham, suffers from over a decade of toxic waste accumulation. This exposure compromises the health and hygiene of Ma Long’s inhabitants. Slum children here risk impaired physical and neural development, affecting their working ability. Insufficient income, therefore, becomes a prevailing problem.

Ma Long residents are unskilled labourers and daily workers. Some pick naturally-grown vegetables for sale. Most residents are children and elderly. The slum is lacking breadwinning working adults.

Thawil, one of Ma Long members, sells Thai desserts for a living. She lives there with her granddaughter.

“I’ve left Nakhon Sawan for decades, but my name is not on a house registration. I do not receive the elderly allowance. I cannot move anywhere because I have to take care of my granddaughter.”

When asked about the Rao Mai Ting Kan scheme, Thawil said she did not receive the aid.

“I do not know how to register, and even if I knew, I could not, because I do not have a house registration. I do not know what to do. Since I came to live here, the district officers visited just twice. Once many years ago and yesterday when they brought instant noodles, canned mackerels, and rice.”

Pong, born and raised in Ma Long, has a wife and two children to feed.

“I worked in a factory, but it is now closed. Now I make finished food to sell at the market. We merely survive day-by-day, but raising a child costs a lot; milk, diapers, all those stuff. Since I was born twenty-ish years ago, I have only received donations twice. The district officers came to distribute basics years ago. Yesterday was the first time since COVID happened. Then today, the Mirror Foundation came for another distribution.”

Not-so-universal assistance

The Mirror Foundation explained that the challenge at hand is perseverance. State- and NGO-led projects must make sure that families of slum dwellers can survive through the pandemic and its impacts. Assistance usually comes in the form of food, but kids and elderlies in these communities also need other essentials like milk and diapers.

On the government’s assistance, Sittiphol said the management is disorganised and does not reach citizens in need.

“State assistance must be universal and not target-oriented. The 30-baht universal health care coverage, for example, came from the idea that everyone should have access to health service. Similarly, the pandemic affects everyone, and all citizens must enjoy equal support from the state. It does not need to be much, just enough for everyone to keep up.”

Sittiphol suggested that the government should also act as a facilitator for citizen-driven assistance. Each district should provide distribution spots to ensure food security and organise orderly handouts. Currently, the government does not make use of its census data nor provide a budget to the local authorities. Help from benefactors gather in the city, but the government does nothing to distribute it to other locations.

Ma Long community and the unnamed slum are but a speck of many unnoticed slums facing the same urgent problems in Bangkok, not to mention numerous others across Thailand. The pandemic sheds light on affected people who remain invisible to helping hands. While the government claims that it “does not leave anyone behind,” it is apparent that these citizens are left behind.