Government’s apathy is going to kill more Thais than COVID-19 does

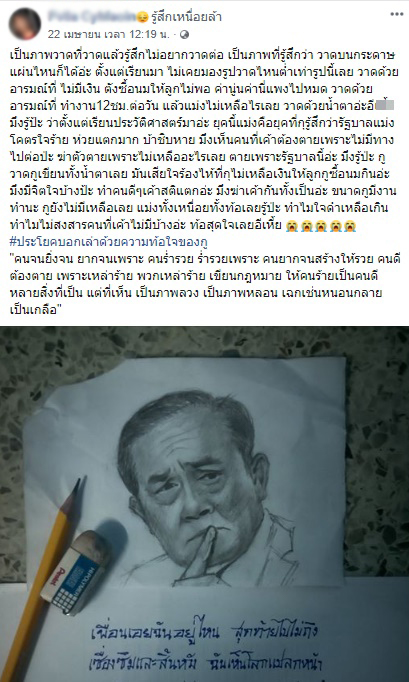

A few days ago, an unfinished pencil-drawn portrait of PM Prayuth Chan-Ocha and its accompanying caption went viral on Facebook. The woebegone rant condemned the government:

“[…] I draw this portrait out of not having any money, not being able to feed my baby. Everything is so darn expensive […] From the entire history class, this government is what I feel to be the most cold-blooded and inept one. It is bloody awful. Do you see people who died as they had no ways of going on? Took their lives because they had nothing left? Died because of this government? I write and draw these with tears. I’m crying because I don’t have money for baby milk. […]”

Shortly after posting this, the young mother committed suicide.

This wretched woman is, unfortunately, not the first to choose this fate. Another debt-ridden mother of two in the Northeast region took her life as the halted economy rendered her income null. A former security guard who lost his job attempted to jump off a pedestrian overpass. A taxi driver, unable to pay taxi installments for two months, hanged himself.

All these tragedies and some others share one thing in common: news reports attribute them to economic privation inflicted by COVID-19 control measures and policies.

Suicide attempts on the rise

Researchers on the urban poor found that during 1-21 April 2020, there were 38 cases of suicides and suicide attempts, a number that got close to the amount of COVID-19 death in Thailand.

The figures came from news reports collected throughout the period. Informal workers made up the majority of those cases. Most of them are of working age and carry the role of breadwinners of their households. In many cases, witnesses cited the delayed and ineffective 5,000 baht compensation scheme to be the perpetrator.

These numbers are evidence, the statement continued, that the government is failing to provide timely and sufficient aid that would have prevented these calamities.

Data from the Department of Mental Health also shows over 12,000 attempted suicides from October 2019-April 2020, jumping from the total 513 cases in 2019.

The spokesperson of the Department of Mental Health claimed that the abruptly rocketed number is due to a change in the data collection method. The 2019 data is under analysis, and the final number could be higher.

Crisis of empathy

Increasing death tolls and cries of desperation do not seem to aggravate the government. While strict lockdown policies and public health measures effectively contain the virus spread, little efforts went to mitigating their economic impacts.

The number of suicide attempts has not yet matched that during the Tom Yum Goong crisis in 1997, said Taweesin Visanuyothin, spokesperson of the Center for COVID-19 Situation Administration (CCSA).

He added that the Public Health Ministry had predicted more suicide fatalities this year, and that the current number ‘did not exceed expectations.’

His remark attracted wide criticism of being insensitive. As a psychiatrist, Taweesin shows lack of empathy towards the loss, according to critiques. The authority he represents focuses on numbers and statistics, and barely mentions the mental health aspects. They omit the critical factor behind many grievances: failure to provide necessary economic aid.

Boorish bureaucracy

The 5,000 baht compensation scheme produced a less-than-desired result. Ineffective screening has turned down ‘informal workers’ or incorrectly branded them farmers, thus disqualifying them. Hundreds of rejected applicants submitted petitions at the Ministry of Finance, yet it remains torpid in reviewing eligibility.

The slow verification and payment process propels desperation. A woman downed a bottle of poison in front of the Finance Ministry after her call for 5,000 baht aid went unheard. One hysteric taxi driver climbed the Ministry’s fence, demanding the payment immediately as he had registered over a month ago.

While expressing concerns, Prasong Poontaneat, Permanent Secretary of Ministry of Finance, accused the protestors of ‘being dramatic’. He claimed that many of them are getting the money, but they try to create a scene to ask for more donations.

“People think we do not take care of them. When they get here, we can only show their status on the website. I am concerned that the media will become a tool for the melodramatic ones trying to get extra money,” said Prasong.

“Even the one who drank poison, she prepared it from home with just the right amount.”

Compassion not allowed

The public sector not only glosses over its inefficiency. When good Samaritans, given up on the state assistance, take it upon themselves to aid the less fortunate, rigid bureaucracy gets in the way.

In Nakhon Pathom, municipal officers stopped a woman from handing out congees. Officers warned that she risked breaking the emergency decree, which prohibits gatherings, despite her claim that she followed the physical distancing procedure and provided hand sanitisers.

“People were waiting, saying that they had nothing to eat and had not eaten on that day, but I could not help them,” said the woman, dismayed by the officers’ treatment.

Meanwhile, in Khlong Lod area, Bangkok, hundreds of homeless people queued up for handouts. City law enforcement officers interfered, saying that the district office had cancelled that contribution spot. They commanded that both receivers and donators to go to another designated location. When the officers prevented the benefactors from distributing food and supplies, an angry and hungry crowd rioted.

Lumpini Park, a regular meeting point of donators and homeless people, put up placards prohibiting handouts and suggested other available donation points.

According to a city law enforcement officer, volunteers and charities must have permission from the district office to distribute food and supplies. Officers will facilitate three rounds of donations per day at designated spots. They will supervise orderly queues for receivers to maintain a safe physical distance.

Brute enforcement of COVID-19 prevention measures may have contained the virus from spreading, but it tends to undervalue another urgent problem. The impoverished are suffering more than ever from economy lockdown and business closure. Insufficient state assistance, or lack thereof, does nothing to relieve their basic needs.

COVID-19 pandemic accentuates the problematic mentality of Thailand’s public sector and policymakers. When citizens are nothing more than numbers, their cries for help fall on deaf ears. More will lose their lives unless the government manages universal, effective aiding schemes.